Top 5 Spots in Wild Beauty

Top 5 Spots in Wild Beauty

24 Nov 2016 |

Of those 26 places, Vanessa has given us her 5 favourite spots from the book - tough ask I know - but she's done it.

1. A Rare Geological Treasure - Mt Narryer, WA

Mt Mt Narryer, a giant fin-like rocky outcrop thrusting from the red desert outback 350 kilometres north-east of Geraldton in Western Australia, holds secrets that open a new window of understanding to the Earth and moon. An international geological treasure, Mt Narryer is one of only a handful of places in the world where direct evidence can be found of the Earth’s original crust. The remnants of the original Earth crust were exposed when an ancient riverbed was pushed up to the surface.

Today, the mountain rises 500 metres from the landscape and is a jumble of multi-coloured rocks including plugs of bright white quartz, dark black specimens and banded red boulders. Fracture marks in tiny fragments of zircon, collected from the rocks at Mt Narryer and nearby Jack Hills, are being compared to similar shock marks in samples collected during the lunar Apollo missions. These zircon chips have been dated at more than four billion years old. They are providing fresh insights into the earliest impact history of the planet, which will in turn confirm the age of oceans, the first water and the formation of tectonic plates as the planet cooled from a molten mass.

2. World's Oldest Living Plant - King's Holly, TAS

Conservationists go to extreme measures in what could be the last chance to protect an Ice Age survivor with a unique mode of reproduction.

Blindfolded and disoriented, all sense of direction is lost to us as we corkscrew into the sky on the windswept extremity of Tasmania’s World Heritage–listed South-West Wilderness area. Our boots have been disinfected, clothes and bags vacuumed clean of seeds and soil, and we have signed a legally binding agreement not to disclose our final destination. It is an elaborate routine necessary to protect the last remaining stand of 43,000-year-old King’s holly, or Lomatia tasmanica – the world’s oldest living plant.

Confined to one location, King’s holly clings to survival on the edge of a rainforest gully, hemmed on one side by a flowing stream and on the other by open heathland that carries the deadly root rot disease Phytophthora. King’s holly has been classified at the highest level of threat by the federal and Tasmanian governments – critically endangered and endangered, respectively. Guided by Tasmanian National Parks’ Ian Marmion, ranger in charge of the area, we are among a handful of visitors who have been to the site.

Perrins predicts King’s holly will become extinct in the wild, the major threats being bushfire and infection. Tasmania also hopes to learn from the lessons of NSW, where the wild stand of ancient Wollemi pine has been effectively loved to death after its location became known and the site was contaminated. ‘With the Wollemi, the idea was to flood the market with them so the wild population was protected,’ Perrins says. ‘But people went in there and Phytophthora is in there now. We don’t want the same situation with this.’ However, Perrins hopes the grafting program will be successful so King’s holly can be propagated and sold in garden centres. ‘We will not be able to use grafted plants as a recovery program [in the wild], but putting it into home gardens means we will not have lost it.’

The dwarf minke whale looms large as we sit on a bar suspended five metres below the stern of our dive boat. Small bumps on the tip of the whale’s nose snap into focus as it comes within centimetres of us before it rolls slightly, holding us fixed in a tranquil but penetrating gaze. It veers past, its exaggerated jaw giving the appearance of a smile.

Dramatic silence amplifies the mammalian exchange. It is an almost otherworldly experience, like floating in space, frozen in time.

We’ve spent almost two hours waiting for the dwarf minkes to display the curiosity for which they have become known. This site, Ribbon Reef number nine, is part of the Great Barrier Reef, about 40 kilometres east of Cooktown. The area is the only place on the planet where dwarf minkes are known to gather in such large numbers – several hundred each year during June and July – but why they do so is one of nature’s mysteries.

‘Dwarf’ is misleading; these amazing creatures measure up to eight metres in length and weigh up to six tonnes. Dwarf minke whales are a distinct species from the better known southern minke whales, which are common in Antarctic waters. They are thought to be a subspecies of the northern hemisphere minke whale and have been observed off the coast of South Africa and in waters off Brazil, New Zealand and New Caledonia. They were first seen on the Great Barrier Reef in the 1980s. Among the smallest of the baleen or ‘great whales’, they are filter feeders: their jaws open wide to reveal a plate covered in hair-like bristles that sieves out small fish and plankton from the ocean.

4. World’s Best Preserved Precambrian Fossil Site - Ediacara Hills, SA

Fossils discovered in the folds of these ochre ranges established a new geological period and a fresh understanding of evolution.

Viewed from the top of Mt Scott, the unsettled landscape of the Ediacara Hills looks like a sea that’s been frozen in time. Deep red bands of rock merge to yellow. Sweeping circular patterns embellish the receding slopes of hills that push to the horizon like the back of surging waves. Part of the northern Flinders Ranges, 500 kilometres north of Adelaide, these large slabs of geological history have been squeezed, folded and turned on end, leaving slopes that roll away into the distance. It was here, 70 years ago, that the discovery of fossils preserved on thin layers of sandstone at the old Ediacara mines site confirmed the existence of multi-celled organisms on Earth between 635 million and 542 million years ago.

Those impressions in rock provided the answer to what is known as ‘Darwin’s dilemma’: how to explain the appearance in the fossil record of later, more complex animals without evidence of their much simpler, multi-celled predecessors. Charles Darwin had theorised the existence of these animals, but it was geologist Reginald Sprigg who found them in 1946. His discoveries were at first dismissed by his mentor, Sir Douglas Mawson, as ‘artefacts of nature’ but later acknowledged after similar specimens were identified elsewhere in the world. They have since been found on every continent except Antarctica in rocks of the same age, but the South Australian find is considered so significant that a period of geological history has been named for it.

5. Ancient Rock Spires - Lost Cities of Limmen, NT

The layered columns glow a mottled golden bronze as they rise from the Northern Territory gulf savannah. More than twice as old as Uluru, the sandstone spires of the ‘lost cities’ of Limmen predate the emergence of complex life forms on Earth. These rock formations are the highlight of one of the nation’s youngest national parks, created in 2012. There are, in fact, two lost cities within the 935,000-hectare Limmen National Park: a southern and a western city; and a third on private land near Cape Crawford.About 1400 million years ago, sandy sediment, later to become rock, began to settle here on the ocean floor. At the time nothing more complex existed than bacteria-like life, which is why the lost cities have failed to yield a fossil record. But we are able to trace, in broad outline, the history of their geological formation. Buried for millions of years, the sandstone was raised out of the sea by the movement of the Earth’s crust.

Today, the city walls may be crumbling but the area is teeming with life. Communities of creatures nest below lacerating clumps of spinifex and take refuge from the sun in deep crevices between the sandstone towers. Some spires near the end of their geological lifespan totter at seemingly impossible angles. Inside the columns the sandstone is much softer and weaker because the silica that binds the rock has been leached away. Over time, these pillars will continue to shrink as the sandstone is eroded. Washed into drainage channels during wet-season downpours, the sand begins its journey to the sea before joining the cycle of deposition and cementation in the Gulf of Carpentaria.

The journey to Limmen is a spectacular drive from Darwin across the Top End to the Gulf of Carpentaria. The unsealed Savannah Way from Roper Bar to Cape Crawford dips and sways past gnarly gum trees that bear witness to a flood-prone past. The stunted gums confirm that soils here are laden with salt, having relatively recently emerged from the sea. The lost cities are evidence of a much older seawater inundation, and of the passage of time itself.

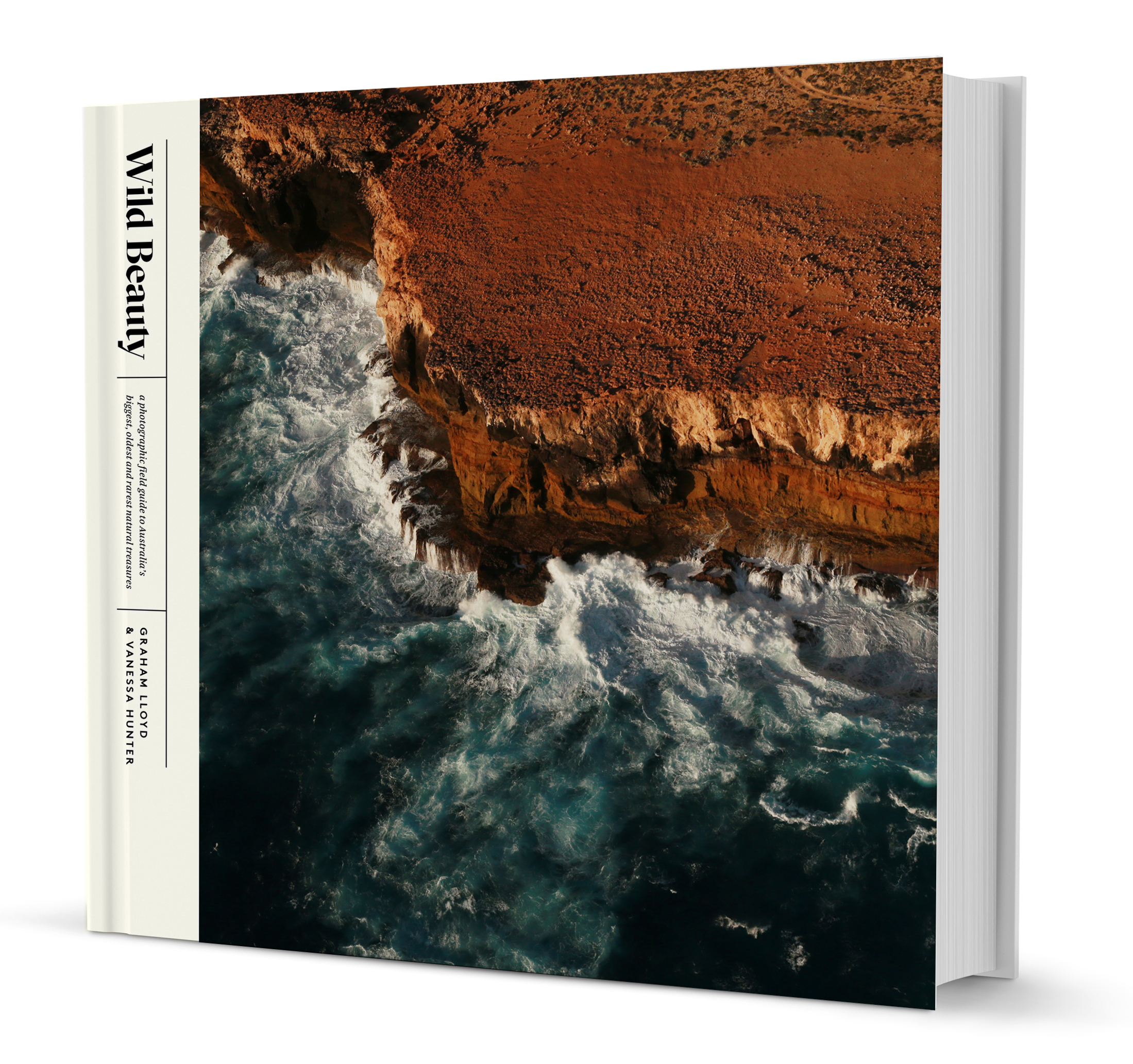

This is an edited extract of Wild Beauty by Graham Lloyd & Vanessa Hunter, Hardie Grant Books, RRP $49.99, and is available where all good books are sold.